Letter to Members of the Notification Committee of the Democratic National Convention Accepting the Presidential Nomination

Albany, N. Y., August 18, 1884.

Gentlemen: I have received your communication dated July 28th, 1884, informing me of my nomination to the office of President of the United States, by the National Democratic Convention lately assembled at Chicago.

I accept the nomination with a grateful appreciation of the supreme honor conferred, and a solemn sense of the responsibility which, in its acceptance, I assume.

I have carefully considered the platform adopted by the Convention and cordially approve the same. So plain a statement of Democratic faith and the principles upon which that party appeals to the suffrages of the people needs no supplement or explanation.

It should be remembered that the office of President is essentially executive in its nature. The laws enacted by the legislative branch of the Government, the Chief Executive is bound faithfully to enforce. And when the wisdom of the political party which selects one of its members as a nominee for that office has outlined its policy and declared its principles, it seems to me that nothing in the character of the office or the necessities of the case requires more from the candidate accepting such nomination than the suggestion of certain well-known truths so absolutely vital to the safety and welfare of the Nation, that they cannot be too often recalled or too seriously enforced.

We proudly call ours a government by the people. It is not such when a class is tolerated which arrogates to itself the management of public affairs, seeking to control the people instead of representing them.

Parties are the necessary outgrowth of our institutions; but a government is not by the people when one party fastens its control upon the country and perpetuates its power by cajoling and betraying the people instead of serving them.

A government is not by the people, when a result which should represent the intelligent will of free and thinking men is, or can be, determined by the shameless corruption of their suffrages.

When an election to office shall be the selection by the voters of one of their number to assume for a time a public trust instead of his dedication to the profession of politics; when the holders of the ballot, quickened by a sense of duty, shall avenge truth betrayed and pledges broken, and when the suffrage shall be altogether free and uncorrupted, the full realization of a government by the people will be at hand. And of the means to this end, not one would, in my judgment, be more effective, than an amendment to the Constitution disqualifying the President from re-election. When we consider the patronage of this great office, the allurements of power, the temptation to retain public place once gained, and, more than all, the availability a party finds in an incumbent whom a horde of office-holders with a zeal born of benefits received, and fostered by the hope of favors yet to come, stand ready to aid with money and trained political service, we recognize in the eligibility of the President for re-election, a most serious danger to that calm, deliberate and intelligent political action, which must characterize a government by the people.

A true American sentiment recognizes the dignity of labor and the fact that honor lies in honest toil. Contented labor is an element of national prosperity. Ability to work constitutes the capital and the wage of labor the income of a vast number of our population; and this interest should be jealously protected. Our workingmen are not asking unreasonable indulgence; but as intelligent and manly citizens, they seek the same consideration which those demand who have other interests at stake. They should receive their full share of the care and attention of those who make and execute the laws, to the end that the wants and needs of the employers and the employed shall alike be subserved, and the prosperity of the country, the common heritage of both, be advanced. As related to this subject, while we should not discourage the immigration of those who come to acknowledge allegiance to our government and add to our citizen population, yet as a means of protection to our workingmen, a different rule should prevail concerning those who, if they come, or are brought, to our land, do not intend to become Americans, but will injuriously compete with those justly entitled to our field of labor.

In a letter accepting the nomination to the office of Governor, nearly two years ago, I made the following statement, to which I have steadily adhered:

The laboring classes constitute the main part of our population. They should be protected in their efforts peaceably to assert their rights when endangered by aggregated capital; and all statutes on this subject should recognize the care of the State for honest toil and be framed with a view of improving the condition of the workingman.

A proper regard for the welfare of the workingman being inseparably connected with the integrity of our institutions, none of our citizens are more interested than they in guarding against any corrupting influences which seek to pervert the beneficent purposes of our Government; and none should be more watchful of the artful machinations of those who allure them to self-inflicted injury.

In a free country, the curtailment of the absolute rights of the individual should only be such as is essential to the peace and good order of the community. The limit between the proper subjects of governmental control, and those which can be more fittingly left to the moral sense and self-imposed restraint of the citizen should be carefully kept in view. Thus laws unnecessarily interfering with the habits and customs of any of our people which are not offensive to the moral sentiments of the civilized world, and which are consistent with good citizenship and the public welfare, are unwise and vexatious.

The commerce of a nation to a great extent determines its supremacy. Cheap and easy transportation should therefore be liberally fostered. Within the limits of the Constitution, the General Government should so improve and protect its natural water-ways as will enable the producers of the country to reach a profitable market.

The people pay the wages of the public employees, and they are entitled to the fair and honest work which the money thus paid should command. It is the duty of those intrusted with the management of their affairs to see that such public service is forthcoming. The selection and retention of subordinates in Government employment should depend upon their ascertained fitness and the value of their work, and they should be neither expected nor allowed to do questionable party service. The interests of the people will be better protected; the estimate of public labor and duty will be immensely improved; public employment will be open to all who can demonstrate their fitness to enter it; the unseemly scramble for place under the Government, with the consequent importunity which embitters official life will cease; and the public departments will not be filled with those who conceive it to be their first duty to aid the party to which they owe their places, instead of rendering patient and honest return to the people.

I believe that the public temper is such that the voters of the land are prepared to support the party which gives the best promise of administering the Government in the honest, simple and plain manner which is consistent with its character and purposes. They have learned that mystery and concealment in the management of their affairs cover tricks and betrayal. The statesmanship they require consists in honesty and frugality, a prompt response to the needs of the people as they arise, and the vigilant protection of all their varied interests.

If I should be called to the Chief Magistracy of the Nation by the suffrages of my fellow-citizens, I will assume the duties of that high office with a solemn determination to dedicate every effort to the country's good, and with an humble reliance upon the favor and support of the Supreme Being, who I believe will always bless honest human endeavor in the conscientious discharge of public duty.

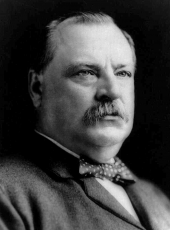

GROVER CLEVELAND.

To Colonel William F. Vilas, Chairman, and D. P. Bestor, and others, members of the Notification Committee of the Democratic National Convention.

SOURCE: Official Proceedings of the National Democratic Convention, Held in Chicago, Ill., July 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th, 1884. New York: Douglas Taylor's Democratic Printing House, 1884, pp 293-296.

Grover Cleveland, Letter to Members of the Notification Committee of the Democratic National Convention Accepting the Presidential Nomination Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/363231